Over recent days the news has been full of stories about severe infections in children with the bacteria Group A Strep (GAS - also known as Streptococcus pyogenes), including tragically several deaths. I will try to summarise our best understanding of what is going on, and some of the pertinent issues.

There is a list of additional resources at the end of the post.

What is Group A Strep?

GAS is a common bacteria which causes infections in humans, but is also commonly found as a commensal organism (meaning it is living harmlessly on your skin or throat). It is well known for causing sore throats (pharyngitis/tonsillitis) predominantly in children, although it is responsible for a minority of cases (up to ~30% in children aged 5 - 15y). It can also cause skin infections like cellulitis or impetigo. It is also the cause of Scarlet Fever (SF), a condition characterised by fever, inflamed tonsils, a rash that feels like sandpaper, and a strawberry looking tongue.

These infections are generally mild, and most would resolve without treatment. However, we do treat some of these cases with antibiotics (especially Scarlet Fever) as it somewhat lessons the duration of symptoms (although not by much), and because it reduces onward transmission and the small risk of complications.

Complications in the western world are mainly associated with the GAS infection becoming “invasive” (so called iGAS). This means it infects a tissue deeper in the body where it can cause more serious illness. This includes infection of the blood stream, of bone or joints, or lungs (causing pneumonia or a condition called empyema). These can quickly result in an overwhelming immune response causing sepsis, which in turn can cause rapid deterioration and be life threatening if not treated promptly. These cases are fortunately extremely rare.

Other complications of GAS are mainly due to aberrant immune response, and include an autoimmune attack on the kidneys (post Streptococcal glomerular nephritis) and on the heart (rheumatic fever). Rheumatic fever is the most serious complication of GAS on a global scale, as it remains responsible for a huge amount of morbidity and mortality in many low and middle income countries. It has almost completely disappeared from many high income countries, but the reasons for this are not clear - it began disappearing before the advent of antibiotics.

What is happening now?

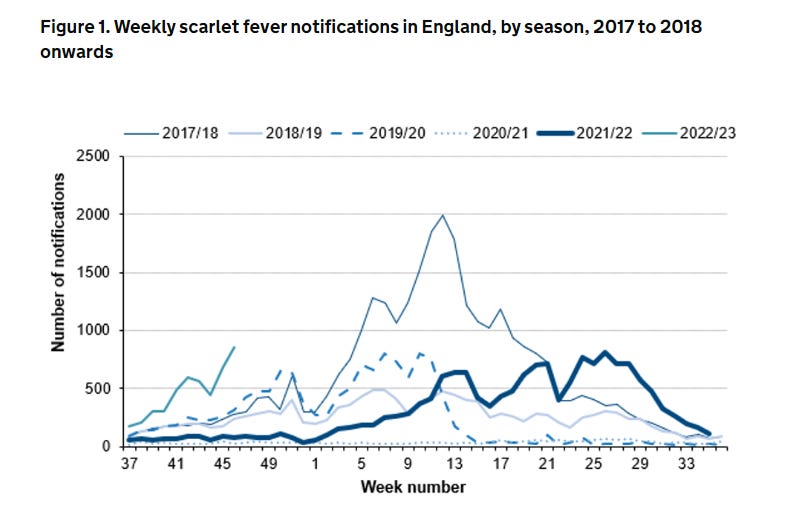

In England, we monitor cases of SF and of iGAS. SF is monitored as it is caused by the same types of toxin producing GAS that are also associated with iGAS. SF is not a concern in and of itself, but high rates of toxin producing GAS in the community may herald increased rates of iGAS.

Population Immunity

We normally get a seasonal wave of SF and iGAS around late winter and spring time. Rates of both conditions almost flatlined for a year during the pandemic. They have now emerged at a different time of year than usual, with very high rates of infection during early winter. Rates are not yet higher than expected during the peak of a normal seasonal wave, but are still rising.

Immunity to bacteria such as GAS is complicated (much more so than respiratory viruses), but could be a contributing factor. Children normally get SF during the first year of school (if at all), and we have a larger cohort of children than usual who have never been infected. Now that normal mixing patterns are beginning to resume, more children than usual have never been exposed, meaning there are lower rates of population immunity and GAS is therefore spreading more readily out of season.

Whilst immunity to bacteria such as GAS is not quite the same as seasonal respiratory viruses, it is believed that immunity is built up over repeat exposure. Whilst infection is very common in children, by adulthood is is rare to even get GAS tonsillitis.

Coinfection

Something else seems to be happening alongside higher rates of infections. GAS does not normally circulate at this time of year, and so is not normally circulating at the same time as the many respiratory viruses currently blazing their way through the population (even more so than usual, also due to lower rates of population immunity following reducing circulation during the pandemic).

Infection with respiratory viruses can increase the risk of bacterial superinfection (bacterial infection occurring on top of a viral one, as damage caused by the virus lets it in more easily) or coinfection (you happen to get both at the same time). As a result, we are seeing particularly high numbers of GAS empyema (when pus collects between the lining of the lungs as a complication of pneumonia), and indeed many of these cases are occurring alongside confirmed respiratory viruses. This has been responsible for many of the most severe cases, and tragically even resulted in the deaths of some children.

There is currently no evidence that a more severe strain is circulating.

What can we do?

This is a very difficult situation. Whilst treating GAS is simple - it is highly susceptible to penicillin based antibiotics - there are 2 problems:

Identifying who to treat

There is currently a very high circulation of respiratory viruses, many of which will be indistinguishable from mild GAS infections of the upper respiratory tract (although symptoms like cough and runny nose make GAS much less likely). Most children will not require any treatment; indeed, antibiotics would make no difference to the course of their illness and may result in side effects such as diarrhoea.

SF is more readily recognised and easily treated. Parents should be aware of the classic triad of sore throat, sandpaper rash and strawberry tongue, and a course of penicillin can reduce the risk of complications and prevent onward transmission. Public health teams will be on the look out for outbreaks, and may begin treating these more aggressively.

Children who develop iGAS may deteriorate very rapidly, but the signs to look out for are no different to the normal advice.

Overwhelming the system

It is very clear from my last ED shift that attempts to increase awareness of GAS have been extremely successful. This causes it’s own issues. It is possible that the biggest danger to children with iGAS is not that their parents don’t bring them to a doctor, but that they are not monitored as quickly or regularly as they should be and their deterioration is missed due to service pressures.

Paediatrics has always been like trying to find a needle in a haystack. Now the haystack has gotten much, much bigger, at a time when we were already struggling to cope with the volume. There is a very fine balance in making people aware of what to look out for, without crushing the system under the weight of understandable anxiety and inadvertently increasing the risk of harm.

What can I do at home?

Firstly, don’t panic! Most children who get GAS will have very mild disease, and complications are extremely rare. Whilst cases are high, two things you can do are:

Encourage and practice good respiratory hygiene, including frequent washing of hands and coughing/sneezing into tissues, and avoiding contact when feeling unwell.

Be aware of when to seek medical advice. This would be if your child has symptoms of SF or if your child is displaying amber or red signs as per the usual NHS advice.

Summary

There are higher rates of GAS circulating than is normal for this time of year, possibly due to reduced population immunity following low rates of infection during the pandemic. We are seeing higher rates of iGAS empyema with viral coinfection, due to high rates of GAS and respiratory viruses circulating at the same time. Children with SF should be treated with antibiotics. Most GAS infections are very mild, but treatment can prevent transmission and lower the risk of very rare complications. The signs to be concerned about have not changed, and include difficulty breathing, difficult to wake up, inconsolable crying, poor urine output (passing urine less than 2-3 times a day), a rash that doesn’t blanch when you apply pressure, fever >38C in a child <90 days of age, or very rapid deterioration.

Resources

UKHSA Group A Strep - What you need to know

Wessex Healthier Together - Group A Strep and Scarlet Fever

UKHSA - Group A streptococcal infections: report on seasonal activity in England, 2022 to 2023

The Conversation - Strep A: three doctors explain what you need to look out for

Thank you for a balanced antidote to the hysteria.

Great summary Ali, cheers