Why are all the kids sick in summer?

Unseasonal surges in respiratory viruses are causing pressure in children's hospitals around the world. What is the cause?

My recent shift in the children’s emergency department was bizarre. It is the start of summer and most children I saw that day were unwell with complaints we only normally see during winter, such as bronchiolitis, coughs and colds, and a fresh wave of vomiting illnesses. My colleagues around the country are experiencing the same thing, and reports from across Europe and the USA are similar.

So why are we seeing all of these winter illnesses during the summer?

It’s complicated!

What follows is a highly simplified explanation of what is a complex and multidimensional system. There are many other facets to this dynamic (such as viral interference, travel and antigenic drift) which I will not delve into here, but we will cover the major factors.

Why do we get “winter” viruses?

The normal pattern of most respiratory viruses is that they predominantly spread during the autumn and winter. The main reason for this seasonality is a combination of the 2 major factors which affect all disease transmission: population immunity, and the nature and frequency of contacts.

Environment and contacts

During the autumn and winter, the weather becomes colder driving social interactions indoors, and more humid which is a more efficient environment for transmission. Schools begin in autumn which significantly amplifies the number of contacts between children. All of this brings more opportunities for viruses to spread.

Immunity

As time passes since the past winter wave of infections, there is a growing population who have gone a long time since their immune system saw the virus, plus lots of new children are born who have no immunity. These people make up the susceptible population. Note that being susceptible doesn’t necessarily mean you have no immunity, just that immunity has waned enough that you can be more readily infected. It is less important how much immunity any particular individual has; we’re more interested in the total level of immunity within the population. Added to this, viruses such as flu are constantly mutating so they look different to when your immune system last encountered them.

Now we have a bigger susceptible population, in an environment more suitable for transmission. This makes it easier for a virus to circulate (R goes above 1) and so the winter wave takes off.

As more and more people get infected, they become immune or their immunity increases again, and this immunity helps drive R below 1 again. Cases subsequently fall.

This is what we call herd immunity, and is one of the main drivers of seasonal waves of infection.

What happened during the pandemic?

As you will all be aware, in order to reduce the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, countries around the world implemented measures such as lockdowns, social distancing, reducing contacts and mask wearing. As you might expect, these measures do not only affect SARS-CoV-2, but also impact the transmission of other respiratory viruses.

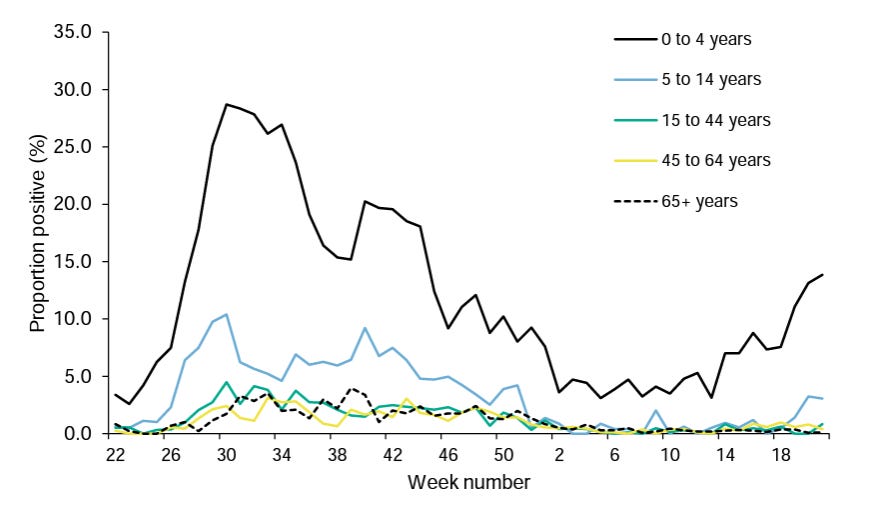

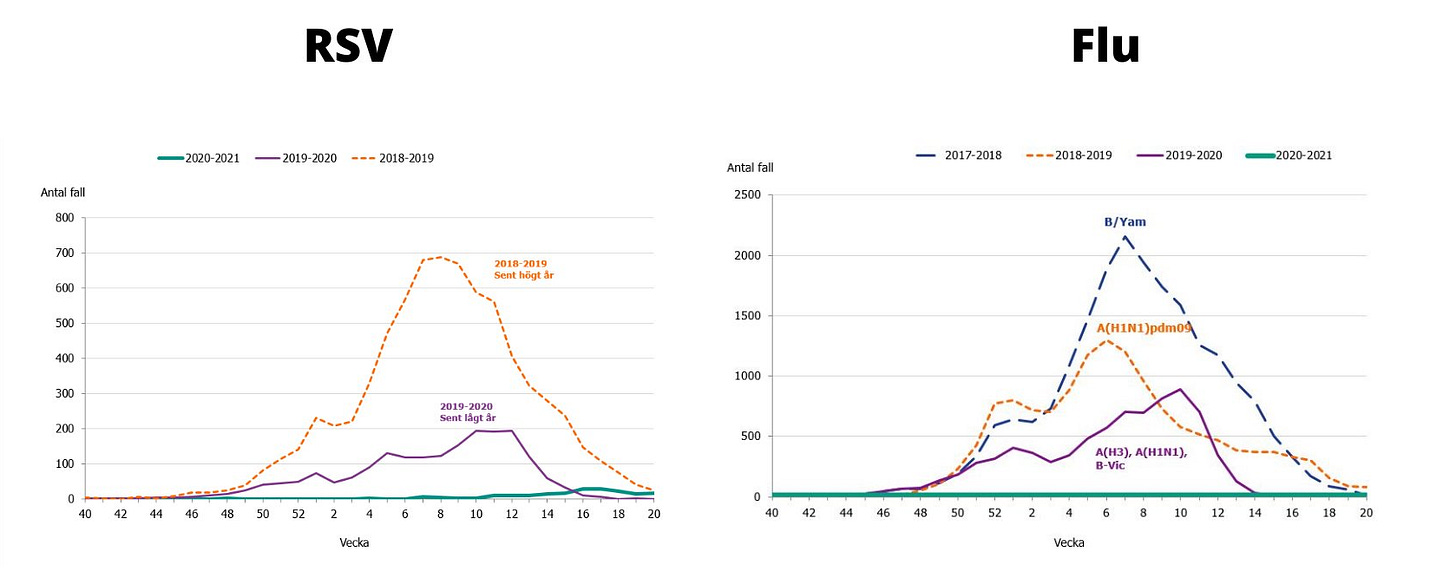

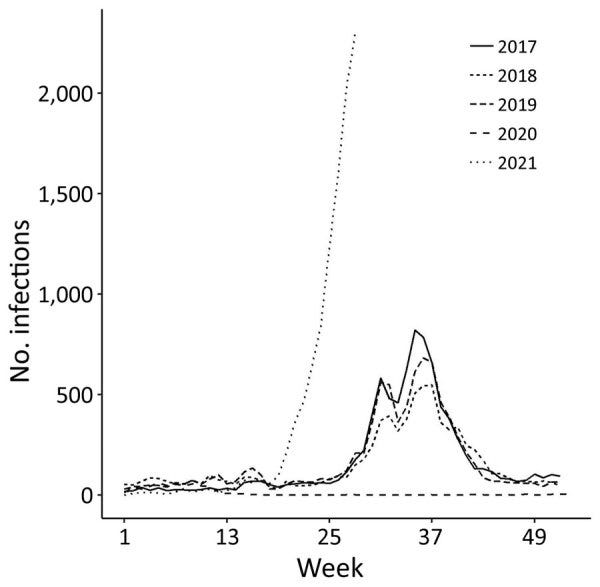

As such, we had a prolonged period where the amount of respiratory viruses in general circulation was significantly reduced. Take a look at the winter season in England 2020/2021 compared to previous years for RSV, Influenza, Parainfluenza and human Metapneumovirus.

If you’re struggling to see it, you’ll find 2020-21 as the flat lines on the bottom.

Of course, during this time period immunity continued to wane in people who had not recently encountered these viruses and more new babies were being born. The susceptible population kept growing for much longer than it normally would, and so grew much larger than during a normal year.

From this point, it would take many more people to become infected than during a normal season to achieve herd immunity, because population immunity is starting from a lower level.

This is scientists are referring to when talking about “Immunity debt”.

We didn’t acquire any immunity through infection for these viruses for a much longer period than usual, so this immunity will need to be “paid back”, to get R below 1 once these viruses are circulating again (all other things being equal).

Displacement

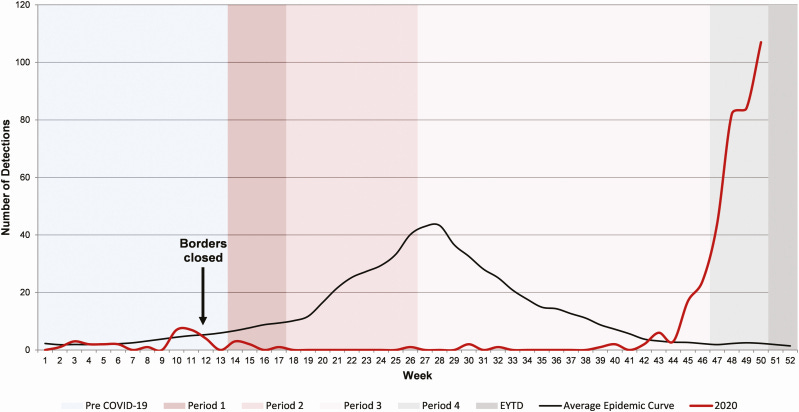

Now it gets interesting. Many countries in the northern hemisphere began lifting pandemic restrictions in the Summer of 2021 following the roll out of vaccinations for Covid-19. This not only allowed Covid-19 to circulate more widely, but also many of the other winter viruses which had otherwise been relatively quiet up until then.

If the UK, we saw an extraordinary summer wave of RSV; the virus most responsible for hospitalising young children in high income countries. Usually it would be very uncommon to see children with bronchiolitis or other manifestations of RSV during summer, and suddenly we had a big wave due to the lifting of pandemic restrictions.

The wave did not look normal, as one might expect given when it occurred. Due to the warmer weather and the school summer holidays, the displaced wave of RSV was not as high as many of us had feared it would be due to the immunity debt, but got flattened out over into the autumn, and actually never quite went away even during winter.

However, since then of course a lot of new children have been born and more peoples immunity has waned - so it appears as though our next wave of RSV is now appearing again during the start of the summer (albeit around 10 weeks earlier than last year).

Worryingly, we have yet to see a resurgence of flu in the UK. Influenza is the cause of major paediatric morbidity as well as mortality in the elderly, and we are approaching the 2022-2023 season with significantly less population immunity than usual. At the time of writing, the first major flu season since the pandemic is just starting in Australia. We are watching closely for signs of what may be to come.

Does immunity debt matter?

If immunity debt just means you need to catch up with infections which were missed before, why is this a problem? Isn’t it a good thing if infections are delayed?

The concern over immunity debt comes from 2 things, both related to the size of the wave.

Too much at once

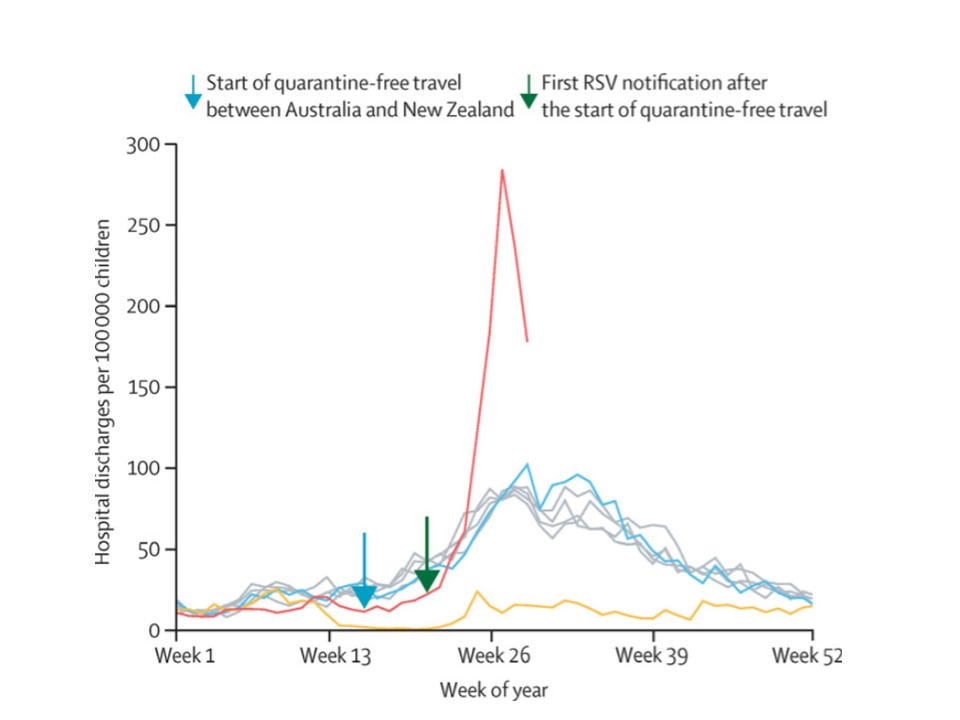

The first is that a very large wave can put intolerable pressure on health services. The size of RSV waves seen in New Zealand for example put so much pressure on paediatric services that unwell children may well have been put at risk. There is a risk of exceeding intensive care capacity and ending up with bad outcomes just because too many people are sick with the same thing all at once.

Overshoot

Once enough people have been infected to achieve herd immunity and get R below 1, infections do not stop happening. The wave simply turns and you get fewer new cases each day, as each infected person infects fewer than 1 new person. All the new infections which occur after herd immunity is reached are called “the overshoot”.

If the wave turns around from a higher total number of infections, there is a lot further down to go. That means that even after you reach herd immunity, a lot more people get infected before cases disappear; the overshoot is much larger. In this scenario, you are not just repaying the immunity debt (i.e. catching up on infections which were previously missed), but you are paying considerable interest on it too (extra infections caused by a bigger overshoot).

Other things can impact on this, such as timing - despite immunity debt for RSV in the UK, the summer timing of the wave meant we ended up with a longer, flatter wave of infections than usual, instead of a very tall and pointy peak (like New Zealand) which would have been much more difficult for health services to manage. For viruses such as influenza, vaccination rates and vaccine efficacy can also play an important role.

What about Sweden?

Sweden is experiencing a similar phenomenon to other western countries with unseasonal resurgences in winter viruses. Some have suggested that since Sweden didn’t implement lockdowns or mask wearing that this cannot be the cause.

Lack of lockdowns or masking is irrelevant, as behaviour in Sweden did change significantly in response to the pandemic in order to reduce transmission of Covid-19. Importantly, they observed a similar reduction in the usual circulation of respiratory viruses such as RSV and Influenza, as was seen in other countries which deployed more traditional lockdowns, with or without mask wearing.

It is the lack of previous exposure to circulating respiratory viruses and lower population immunity which has caused the displacement of respiratory viruses, so this is precisely what we would expect to see.

Shouldn’t it be back to normal by now?

Others have suggested that because schools have been in session for a year now in the UK that these dynamics should have settled down by now, and so cannot be explained by decreased population immunity. This is not true.

Because the normal patterns have been so grossly disrupted, even once we reach herd immunity (for example, after last years summer wave of RSV), the timings of when this immunity declines and shifts with weather patterns is completely distorted, and will take some time to shift back into it’s usual dynamics.

During this time we are also still making lots of new babies who have no immunity (babies <6months may often have some immunity given to them by their mothers by placental transfer during the third trimester, but as fewer mothers have had recent exposure to RSV this will also be less than usual).

Surely it’s just all due to Covid-19!

As many people are now very focussed on Covid-19, there is a temptation to blame almost any usual epidemiological events on this disease. The truth is Covid-19 cannot explain this phenomenon. The first places that displacement and immunity debt were demonstrated were in Australia, New Zealand and Japan, where a negligible proportion of the population had been exposed to Covid-19 at the time this occurred.

Summary

Pandemic restrictions prevented transmission of other respiratory viruses for quite a long time, leading to a lower than usual population immunity (immunity debt). Upon reopening these viruses surged again out of season, and are now in unusual patterns, including many winter viruses appearing during summer. It will take some time for viruses to settle back to their previous dynamics. We should be concerned about a resurgence of Influenza this winter, especially if it coincides with a large seasonal wave of Covid-19.

Thank you so much for your insights. I look forward to your posts on Twitter. I have been fascinated by the shifts in viruses as well. I’m a pediatrician in southeastern United States. We experienced a huge wave during delta which was very scary because the adult beds were being taken up by delta and the ped’s beds by rsv.

I am more inclined to credit viral interference for the shift of the viruses:

1) the drop off in all other viruses happened prior to wide spread masking or social distancing. Excellent article by Dr. Christopher Harrison, infectious disease at UMKC (Kansas City, MO) which demonstrated every virus falling off early March except rhinovirus which he called the cockroach of viruses. 😂

2) most transmissions happen in the home setting. Therefore, the weather only plays a role via humidity and not personal behavior. Also, I’m in the south and we are a slovenly group who stays inside most of the time anyway!

This study has fascinated me because it is a retrospective study looking at how viruses interact and how they can shift the spread of other viruses. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34968374/

I’m also personally doing a study of rsv/Covid in the outpatient setting. I’m looking at rapid antigen testing of those tested for rsv and Covid. So far, none are “co-infected.” I think the hospital numbers showing coinfection are skewed because they are often pcr. This may pick up an infection as far back as 6 weeks prior and doesn’t represent which is the cause of their hospitalization.

Thank you again for your work and your reasoned response during the pandemic.

Thank you! Fingers crossed for next winter’s flu season. I imagine the NHS is doing the same!